Categorizing Cultural & Creative Sectors: An Impossible Task?

Panel discussion on the Creative FLIP closing event

It is one of our most fundamental cognitive abilities to identify shared features or similarities of objects, events, or ideas and then to group (“categorise”) these to make sense of the world. Without categorisation, learning, language, memory, and decision making (to name a few only) would be impossible. The production of cultural statistics also depends on categorisation, distinguishing what is to be measured and what is not.

Session: Categorizing CCS - an impossible task?

In this panel on the FLIP FORWARD Final Conference organised together with the CHARTER project (See: Factsheets: Families of competences pdf), we want to discuss the benefits but also the dangers of categorisation related to the self-image, the measurement, but also the visibility of the CCSI: categorisation enables a highlighting of similarities, but it also has the potential to exclude the unforeseen, the evolving, the fringes.

Our discussion will focus on cultural-creative occupations and be organised around the following questions:

- To what extent do the categoriser’s viewpoint and goals shape the categories?

- What are the limitations and dangers of categorising the occupational scope of the CCS?

- Is it possible to develop an occupational categorisation of the CCS that serves all purposes? If not, how do you deal with this dilemma?

Are you in Brussels on 15-16 November? Interested? Get in touch.

One of the most fundamental problems of developing creative businesses in Europe and developing public policies to support them is that we have far less business and policy planning information available then any business in fruit farming, manufacturing of cars or providing banking services. Cultural statistics have a very low coverage in music or film. Indicators that an apple producer, a car component manufacturer or a bank supplier can take for granted, such as total or average gross value added in a country, employment, or wage statistics, do not exist.

The lack of statistical coverage makes it particularly difficult for such creative businesses and their industry organisations to comply with the expectations of the Corporate Social Responsibility Directive or participate in the advantages of green financing and the European Green Deal.

The production of statistics for the music or the film industry, like any other industry, relies on three fundamental categorisations:

the categorisations of economic activities that creative businesses and self-employed people do;

the categorisations of their products and services (such as films or sound recordings);

the categorisation of occupations and jobs available or filled with such occupations.

These categorisation do not work well in the cultural and creative sectors, and perhaps in some other services sector either.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/photos/person-selling-vinyl-album-in-street-QBvtgLdmTbQ?utm_content=creditCopyText&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=unsplash).](/media/img/blogposts_2023/jan-demiralp-MH8-fg_P7Fo-unsplash_2x1_hua1b1758c074217d07001258b5fd46934_434866_5a872ebdee4dcf343403f17296eaac85.webp)

Why normal business and occupation categories fail to work in the creative sectors?

Unfortunately, these categorisations cannot be successfully applied in the music or the film industry for many reasons:

- The entities are too small.

- They have mixed activities.

- They mainly employ people atypically without even checking their formal qualifications.

A small recording studio that works for films or the music industry, or a small company that offers stage or in-studio or on-set lightning typically employs people who learned their skills on the job; they often do various related activities, so their NACE code is not very characteristic. Also, because of their size, they hardly ever participate in governmental statistical surveys.

On a more fundamental level, in the creative industries, the dominant firm size is the microenterprise, where the management functions are usually not specialised and often not filled by people with business administration degrees: they do not have an HR department or even an HR function that would categorise their jobs; they do not have a management controlling system that would rely on a sophisticated bookkeeping or a well-categorised inventory of sales. This is what the International Labour Organization, or employment policymakers, describe as “informal enterprises”: they do not have formal internal structures, processes, and often even contracts that in larger enterprises enable a professional management of product, career, finances, or sustainability.

To help small enterprises in music or film, we need different data collection and statistical or indicator production procedures and more flexible categorisation processes to support their business development on enterprise or a regional/national level.

to the business-to-government data sharing, novel re-use of public sector information for the creation of missing marco-, industry-, and institutional KPIs for the Slovak cultural and creative industry strategy implementation documentation. Download: [DOI 10.5281/zenodo.8399254](https://zenodo.org/records/8399254).](/media/img/blogposts_2023/slovak-cult-stat-pilot_screenshot_hu894523d7215bb41d17bf3853b9fa740b_111820_309b4827783dbf37ea514f7376a00c4a.webp)

In Open Music Europe, building on a decade of experience at the Digital Music Observatory, we are using statistical processes and data innovation to serve the needs of the music industry by providing data on royalty collection, marketing, average artist remuneration, or gross value added. Our approach is based on innovative statistical procedures and recent regulatory changes that allow national statistical authorities to embrace them.

We do not have average musician remuneration statistics or gross value-added figures for music labels because even though musicians and record labels participate in the national statistical system, they are invisible as they do not have a clear category. The NACE categorisation system does not contain the activities of the “music industry”, only categories like “audiovisual” or “art performances” categories that mix up the numbers of the music industry with television, video production, or theatres. The same can be said of most occupations where music businesses employ workers or self-employed professionals. Even though they have a chance to participate in statistical surveys, which call upon a randomly selected list of small enterprises (in the case of business surveys) or people (in the case of the labour force surveys), they do not get an appropriate “musician” or “music business” label.

The categorisation or labelling of “performing arts” or “audiovisual” is unsuitable for a musician or filmmaker. If “audiovisual” average wages rise in a region, who are they supposed to know if this is due to outsourcing some film post/production to the region or an uptake in music recording activities? After all, film sound studios and music recording studios work for different markets and employ different people.

On the other hand, many creative industries know who belongs to their industry. Architects usually must fulfil severe qualification requirements and register into a local chamber of architects. Musicians must register with author’s and performer’s collective management societies if they want to receive copyright or neighbouring right royalties. If we can align such representative creative organisations with the statistical processes, we will get indicators that follow relevant categorisations for musicians, record labels or architects.

Several statistical and data innovations can make such an alignment or data coordination possible.

. _European Business Statistics Methodological Manual for Statistical Business Registers_. [2021 Edition](https://doi.org/10.2785/093371).](/media/img/blogposts_2023/statistical_innovation_publications_2x1_hud9e1e237b2bc105a2f1906776cab1691_508928_081a4837f39432737d8bc43e217b328c.webp)

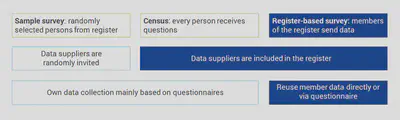

Sample surveying, when musicians (as members of the working force) or their enterprises (as small businesses) are selected by a lottery to fill out a questionnaire, had been the most important source of official statistics between 1970 and 2010, but they are less and less used. Before the 1970s, we only had fewer statistics on full census-like questionnaires with no random sampling. In the last decade, we have seen more and more often that statistical offices directly connect to various “registers” or databases initially created for business or tax administration purposes to retrieve the data. Why ask a musician about her royalties if we can access her royalty account directly?

From a royalty account, we can access more precise and timely information than from the memory of an artist.

In the last decade, UNECE and Eurostat have been the forerunners with several European national statistical offices in finding new ways to tap into so-called “privately held” registers, for example, the royalty accounts of copyright management societies, who have a full view of musicians in the country and precise and relevant information about their earnings, and indirectly about their employment or gross value added.

](/media/img/blogposts_2023/banner_slovak-cult-stat-pilot_hudeb81031bc81f32b6c2c889dd2eec5a6_763762_6ae388fe9896d5259e2a6d2e6ff43c20.webp)

In Slovakia, we are working out a process where the register and framework of the official data collection could be aligned with a private register set up by the music industry’s nationally representative stakeholders. Such a scheme would have many advantages both for the private and the public parties:

The collection of the statistical data would be faster, cheaper and more precise.

The data could be securely mapped to and from the NACE/ISCO categorisation used by the government and the relevant categorisations used by the music industry.

Whenever the music sector – a relatively minor part of the services business sector – would be under-sampled in a statistical survey methodology to produce reliable, music sector-specific data, additional, harmonised surveys or administrative data could ensure that minimum amount of music enterprise and musician data is present for quality-controlled statistical indicators.

The music businesses could professionalise their company planning HR processes, and, critically, have relevant benchmarks for environmental and social sustainability management; they could participate in the European Green Deal.

Cover photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash.