TextileBase

A platform to collect, connect, and share meta- and research data on material, visual, and textual sources of historical clothing

Seto garments in the Obinitsa Museum, Setomaa, Estonia

Seto garments in the Obinitsa Museum, Setomaa, Estonia, [Q180](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q180), [Q179](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q179), [Q181](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q181).](/media/png/dataspace/textilebase/Textilebase_four_images_hud9c1ab3a1a107b842d90f84f6576b635_244654_c7d8e4451d5ce9ff2a6b3c6620e7010a.webp)

«««< HEAD Textile research helps us understand how people live, adapt, and express themselves. By studying what people wear and how fabrics are made and traded, we uncover stories of culture, identity, innovation, and global connection. In 2025, as environmental and social sustainability become ever more urgent, learning from the past and present of textiles can inform better decisions in fashion, labour, and the environment. It’s not just about clothing—it’s about how threads connect us across time and place.

The development of TextileBase compels us to address complex challenges in data curation, validation, and interoperability—issues that are highly relevant across both commercial and academic domains. Because most textiles have a relatively short lifespan, their study often relies on secondary sources such as technical and artistic drawings, colour plates, and photographs that document how textiles were made, used, and worn. These sources introduce multimodality: our system must integrate and relate knowledge drawn from physical artefacts, digitised images, and descriptive texts. Moreover, the data originates from a wide range of institutions—research centres, museums, archives, and libraries—each employing distinct metadata standards. TextileBase is therefore not only a tool for textile historians, but also a model for handling complex, multimodal, and decentralised data in broader sectors.

The first published dataset, Linked Open Datasets on Garments from the Latgale Region contains data on Latvian traditional shirts and skirts from the Latgale region in Eastern Latvia. The female and male shirts, and the skirts in the dataset are handmade and were worn in the 19th century. They represent both festive and daily wear of the local female and male peasants. The shirts are stored at the National History Museum of Latvia and the Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia. The data contain information on the locality of their origin, their approximate date of creation with various precisions, the materials they are made of, and the way of their fabrication, as well as their purpose of wearing (festive or daily wear) and wearer’s ethnicity and gender. They also include the name of the museum each shirt is stored at, supplemented with its unique inventory number. Data on some sample shirts also include a photo of the shirt.

A Semantic Knowledge Graph for Textile and Dress History

2e3d90dfbfa8fae4b2d532c2d8067737a2653b7c

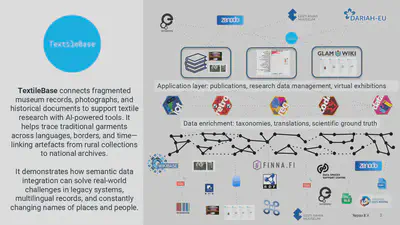

TextileBase is a knowledge graph that interconnects databases and secondary sources—such as artefact photographs, contemporary images, drawings, and written descriptions—related to textile and dress history. It supports diverse areas of textile research, from historical dress studies to sustainable fashion.

«««< HEAD

- See every entry in the database: All items

How TextileBase Works

TextileBase is an intelligent, modular system designed to support collaborative textile research and data sharing. Its main interface is a user-friendly Wikibase instance—built on the same software that powers Wikimedia projects—which allows researchers and textile enthusiasts to record, link, and validate knowledge.

Behind the scenes, TextileBase integrates advanced methods from digital humanities. It uses an ontological data model based on CIDOC-CRM, RiC, and DCTERMS, ensuring semantic interoperability with museum, archive, and library systems.

TextileBase s supported by a graph database and an experimental SPARQL endpoint. This enables translation of its structured data into linked data graphs, which can be enriched and exchanged with heritage institutions.

The system is multilingual by design. By leveraging international thesauri and computational linguistics, TextileBase supports cross-language discovery—essential in regions like Latvia, where historical textile records exist in multiple languages and scripts, and artefacts have travelled widely across Europe.

Data import and export are powered by Reprex’s data curation and cleaning libraries. This modular design supports workflow automation and the integration of diverse, hard-to-find, multimodal sources. TextileBase is built to scale: it is cost-efficient, open-source, and adaptable for academic, commercial, or industry research teams of any size.

Technically speaking, building an interactive website for textile history is like setting up a webshop—except all the product information is either missing or fragmented. There are no barcodes, producers, or standard descriptions. Instead, the relevant information is buried in academic knowledge, secondary sources, or scattered fragments of primary data.

This is where AI can significantly assist: by gathering, linking, and inferring data at a speed and scale beyond human capacity.

Connecting Surviving Artefacts

Unlike metal objects or buildings, textiles are fragile and rarely survive intact. They are worn, used, and discarded. Even from the 19th century, very few textiles remain.

Our goal is to create a tool that connects fragmented museum inventories and catalogues across institutions—linking rare textile artefacts in a coherent, searchable network.

The Challenges of Linked Open Data in Textile History

While digital humanities frequently refer to “linked open data” or the “Internet of Things,” textile history is still at the early stages of adopting these frameworks. A key goal of TextileBase is to give each artefact—like the Seto shirt—a unique URI. But generating URIs for garments in small rural museums or private collections is often time-consuming and expensive.

TextileBase seeks to streamline this process—making it faster, cheaper, and more reliable.

). For example, Aladár Bán collected a somewhat similar shoe in Setomaa in 1911. Finding that artefact in the digital collection of the Hungarian Ethnographic Museum in Budapest under the inventory number [NM97021](https://gyujtemeny.neprajz.hu/neprajz.01.01.php?bm=1&kv=3300296&nks=1) and the rather specialist and bit archaic title „bocskor” is even a challenge for native speakers of that language. It is connected to the other Seto footwear as TextileBase [Q348](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q348).](/media/png/dataspace/textilebase/_hu0383cfdd17bc06a1a5c9b965698b5240_1109255_20c9a87e2e41770c6b30499786cc46a1.webp)

The Importance of Secondary Sources

Historical collecting practices were often biased. Textiles worn by everyday people—peasants, laborers, minority groups—were rarely preserved. Instead, most surviving collections reflect the lives of elites or were gathered during ethnographic expeditions with colonial or exoticizing perspectives.

That’s why secondary sources—such as period photographs, illustrations, and books—are so valuable. They often unintentionally document everyday garments, offering insights missed by early collectors.

) is a detail from the photo collection of the Estonian National Museum’s item Johannes Pääsuke: Seto men in the village of Võmmorski in Setomaa municipality (1913). The original photo: *Setu mehed Võmmorski külas Setomaa vallas*, [ERM Fk 213:172](https://www.muis.ee/museaalview/610034), Eesti Rahva Muuseum (in TextileBase [Q332](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q332)).](/media/png/dataspace/textilebase/028747_ERM_Fk213_172_028747_original_detail_huecdf2f0ae34751b4bdf3298385c056a4_1719822_6f74e42639618b928a70983804de34e0.webp)

Case Study: Finno-Ugric Traditional Clothing

We focus on the clothing traditions of small Finno-Ugric communities—such as the Setos and Livonians—due to the technical and linguistic challenges involved.

For example, Livonian communities in present-day Latvia were largely assimilated by the late 19th century. Setos are now found in southeastern Estonia and Russia’s Pskov oblast. Their artefacts are scattered across Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian archives, usually documented in those languages—rarely in Livonian, Seto, or even English.

; in TextileBase [Q347]((https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q347)) has a provenance information of Venäjä, Kuurinmaa, Pissen, Piza; which means roughly Russia, Courland, Pissen, Piza ([Q346](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q346)). This is Finnish language information recorded in the early 20th century about the Courland region of Imperial Russia using the Baltic German and by now moribound Livonian village name. That village is known today as [Miķeļtornis](https://reprexbase.eu/textilebase/Item:Q346) in Latvian (local Livonian spelling: Pizā), Courland is known as Kurzeme, and of course, the country is Latvia.](/media/png/dataspace/textilebase/_hu738d4ad8ec0ad05ec3b7ce83df1ce8e6_1860996_3e791d5bcc9999954129f6601ce9a5d1.webp)

We must build a historical namespace of place names, languages, even spelling history, and garment classifications to search and understand this data. This includes terms like “shirt” in Finnish (paita), Hungarian (ing), or Estonian, and accounts for changing styles, materials, and local terminologies. This is one of the uses of TextileBase: it contains knowledge about words, placenames, their morphology, so that researchers not familiar with the collection’s language (and its historical changes, abbreviations) can work globally.

What Business Can Learn from TextileBase

You may think this is a niche academic project. But the challenges we tackle—changing place names, multilingual records, incomplete legacy data—are universal in business.

When a company acquires a legacy system, it spends time and money just fixing inconsistent addresses.

Global databases face problems when towns merge, streets are renamed, or countries change borders.

People change names, too: marriage and divorce often change surnames. Rights are inherited by descendants who may or may not use the same surnames, making long-lived copyright claims particularly difficult to trace.

Searching for “a skirt from Venäjä, Kuurinmaa, Pissen” is equivalent to finding a misfiled invoice or product from a renamed supplier.

Our work shows how semantic technology and AI can solve real-world problems across industries—by cleaning, organizing, and making sense of historical or fragmented information.

Building a Wikimuseum for Dispersed Collections

Inspired by Wikimedia Estonia’s multi-language, open-access model, we propose a virtual museum—a Wikimuseum—that brings together:

Artefacts from rural museums (e.g., Mõniste, Saatse, Värska)

Items in national museums (Estonia, Finland, Hungary)

Private collections that would never be physically exhibited together

This approach connects dispersed knowledge—across time, languages, and borders—into a shared digital space.

How AI Supports Textile Research

TextileBase incorporates AI-driven tools—language models, translation engines, inference systems—that can:

Search for historical placenames across multilingual archives

Identify garments in photos or scanned books

Detect and match synonyms or spelling variants

Flag potentially relevant images and documents for expert review

By operating within the TextileBase framework, our AI tools remain human-controlled and explainable, reducing the risk of hallucinated or misleading results.

2e3d90dfbfa8fae4b2d532c2d8067737a2653b7c