SKCMDb

Find All Music Ever Made in Slovakia

.](/media/posters/IAML-reprex-poster-2025_hu29650834c1f466e3d24bbd103225d8fb_3179691_01169f53faf069cb2891f0b0e3cd648a.webp)

Check out the entry examples related to Albrecht’s: Missa in C (printed, Hudobné centrum) with library and webshop access points, and linked data on the composition itself Q479, linked to its recorded manifestations.

Early Data Access

Wikibase Interfaces

with library and webshop access points, and linked data on the composition itself [Q479](https://reprexbase.eu/skcmdb/Item:Q479), linked to its recorded manifestations.](/media/png/skcmdb/skcmdb-missa-in-c-print_huc02e499568671c38186b5b9e9bb715fb_116971_9b9408a78c763bdbbe8eeb69fb5db1fc.webp)

In machine-readable TTL format: https://reprexbase.eu/skcmdb/Special:EntityData/Q485.ttl In XML or JSON, JSON-LD, N-Triples.

SPARQL Endpoint

http://135.181.91.51:3030/#/dataset/skcmdb/query; requires password.

Sampo Semantic Browser

](/media/png/skcmdb/skcmdb-library-access_huf3155c55aaf98b7cdd63ae10eaa747e0_109899_44f93947517fcf22ddbe6ef033eed7cf.webp)

Next steps

The Slovak pilot illustrates how libraries and national music centres can take a central role in a decentralised European Music Observatory that federates with the EU Open Data Portal, Europeana, ECCCH, DARIAH, and Zenodo. This poster accompanies a companion contribution on the Finno-Ugric Data Sharing Space, including the LīvMDb (Livonian Music Database), which explores how smaller regional repertoires can be embedded in broader, multimodal cultural graphs—advancing the vision of a European Music Observatory as a complement to the European Cultural Heritage Cloud.

Project History

In 2020, we studied the effect of increasingly AI-driven streaming platforms on the Slovak music repertoire. We realised that music is being recommended by algorithms, not only to YouTube or Spotify subscribers but also to radio editors, concert promoters, and festival organisers. We realised that rights management organisations (CMOs), music information centres (MICs), and music libraries, archives, and documentation centres (MLs) must change their practices to remain competitive and visible.

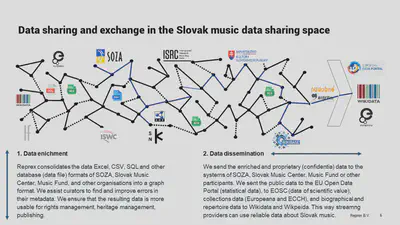

In the Open Music Europe project1, we are building a data infrastructure that aims to coordinate music knowledge (in our demonstration example, Slovak music) stored in various institutional silos and systems. We wanted to “plug in” the database of the MIC Slovak Music Centre (MCS) into a global data system like Wikipedia or Spotify and, at the same time, connect it with the Slovak CMO SOZA, the Slovak National Library and the music section of the ML Bratislava City Library. A data science company, Reprex, oversees this process.

We want to ensure that a MICs and CMOs have the most accurate information about music. Whenever data is missing or new information has yet to reach their database, we try to look up the data from reliable sources and ensure that it arrives automatically in their system (to be reviewed by a knowledgeable human curator).

Make all music in Slovakia visible on all global music systems, encyclopaedia, Europeana and the European Cultural Heritage Cloud. Enable people to locate sheets of works for sale or public lending and show where people can listen to the music in various formats.

Provide the information in a dual format: enable a MIC to provide machine-readable, standardised, RDF annotated data to directly support the recommender systems of Spotify, YouTube, Deezer and other platforms.

Provide CMOs with a framework to make their members more visible to digital streaming platforms by enrichment, control and processing of available metadata and to also inform radio stations about the potential recordings that count into their local content, thus promoting local CMO members.

As seen from the points made above, this data infrastructure is beneficial to a great degree for all the parties involved.

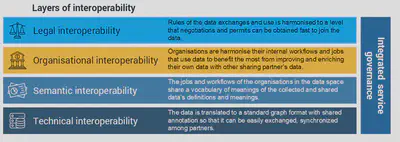

European Interoperability Framework for Music

Nowadays most data is downloaded and used by intelligent software agents on various digital services and platforms. To meet the modern service requirements of 2025, we needed to implement an enhanced implementation of the European Interoperability Framework (EIF) that extends to privately held data. We need to communicate information and metadata about Slovak music in a way that musicologists, musicians and their managers, copyright law practitioners, citizen scientists as well as software agents understand worldwide.

The EIF is a four-layered specification for how to create world-class digital public services. In music, however, the private sector is vital, too. CISAC’s members, the CMOs that register new works, are private parties. To add weight, digital streaming platforms ingest more metadata about music in a week than Europeana Sound over ten years.

To ensure legal and organisational interoperability, the members of the Open Music Consortium (SOZA–Slovak Performing and Mechanical Rights Society, MCS, Reprex) signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Slovak Ministry of Culture; later, MCS, SOZA and Reprex signed a more technical MoU with the Slovak National Library2.

The aim at the legal level was to understand the different rules of business and statistical confidentiality, as well as data protection rules in general. Harmonising the GDPR across a public information body like MCS and a private entity like SOZA is particularly challenging.

On the organisational level, we must ensure that different organisations (MCS, SOZA and the national library) understand each other’s data and workflows, for example, in identifying a musical work or a musical group with no legal personality.

On the semantic level, we must ensure that the databases of MCS, SOZA, and the national library understand each other.

The technical level must ensure that harmonised workflows result in successful data exchanges, given the legal constraints and semantic definitions.

Music Data Sharing Space

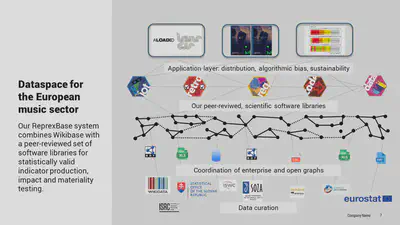

In our system design, we followed two important new European initiatives. In connecting cultural data, European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCH), and the Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory. Concerning connecting authoritative data across governmental and private systems, we adhere to the novel European data governance regulations3.

A data (sharing) space is a system that integrates data whenever it is needed, or is permitted, with some labour-intensive aspects of data integration postponed until it is possible to carry them out. In a data sharing space, like Reprex’s Motion Picture Dataspace, we know where the data is in each organisation, we know its format, documentation standards, even known problems and issues. But we only load them into an application, for example, an application that calculates environmental effects or GHG emissions when it is needed and permitted. Our dataspace reduces the work in such scenarios by by setting up automatic matching and mapping generation techniques4.

Wikibase is the software that runs the worlds largest open knowledge graph database, Wikidata, which synchronises knowledge with about 330 (different language) Wikipedias and countless national libraries, music services, and other data sources. Our dataspace is powered by an extended and configured Wikibase system. Wikibase has often been used for authority control; it is also the system of the EU Knowledge Graph5.

The most notorious problem plaguing digital services and databases is the unresolved issue of named entity disambiguation. With digital services providing access to over 100 million recordings, we often find dozens of artists or works with the same title. Named-entity ambiguity is confusing for humans and for autonomous AI systems, too.

Our system focuses on harmonising the registration processes of various knowledge organisations, such as libraries and CMOs. We want to ensure that every artist, music group and the manifestation of their work in music recordings and sheets receive a globally unique and persistent identifier. We want to provide new recordings and sheets in at least one public library with a globally used VIAF (and, when applicable, an ISNI) identifier. To support named-entity disambiguation going back to hundreds of years of music creations and events diaries, we are developing trustworthy AI systems that remain strictly under human control in line with the new requirements of the EU’s AI Actt6.

Disseminating information

Returning to our Feasibility study, we realised that about half of the music streams had data problems. They resulted in late or missed royalty payments. We also realised that almost a fifth of the Slovak repertoire had such low-quality metadata that music recommender systems could not make sense of what their recordings work. We are changing this situation. We want to ensure that we realise if the “Internet knows” misleading information about a work or recording. Using modern data-enriching techniques, we ensure that the MCS and SOZA have the most accurate 360° views of the repertoire they represent. By data dissemination, we also guarantee that digital streaming services and search engines are informed about precise and up-to-date knowledge.

- We carry out health checks on the metadata of artists and labels and highlight missing, potentially misleading, or erroneous information.

- Utilising Wikidata and Wikipedia, we disseminate the correct information to streaming services and search engines (which rely on knowledge graph technologies and regularly crawl Wikidata.) We are hosting a Wikipedian in Residence to find better cooperation with the Wikipedian community and the curator community of Wikidata.

- We are building the Slovak Comprehensive Music Database (SKCMDb) that will inform radio stations about the potential recordings that count into their local content (legally stipulated) broadcasting quota, where orchestras can find for purchase or public lending scores of works or where professional and enthusiast audiences find any music ever made in Slovakia.

- We are designing a new digital distribution model for non-profits and self-releasing artists who need help receiving professional service due to the low commercial value of their culturally valuable works.

- We are also experimenting with data bias checks to find out about potential algorithmic biases that work against the Slovak repertoire.

Our Demo

Context: Open Music Observatory

Our ambition with the development of the Open Music Observatory is to provide the technological basis and a practical roadmap for creating a European Music Observatory in a bottom-up, decentralised way. Instead of waiting for a grand, central agreement on what should a European music observatory be collecting and who should control it, we suggest a pragmatic approach: allow any data owners and collectors who satisfy certain quality and cooperation rules to add their data to an Open Music Observatory; when it reaches a sufficient maturity for use in Europe, then decide if its maintenance requires a new institutional form or not. You can read or regularly updated progress report on this work here.

Creating the Open Music Observatory is a cornerstone task of the Open Music Europe (OpenMusE) – An Open, Scalable, Data-to-Policy Pipeline for European Music Ecosystems (Open Music Europe 2023) Horizon Europe research and innovation project. This task is running till the end of the project (31 December 2025) with the collection, processing, and dissemination of more data and providing innovative, new data services in line with our exploitation pathways. This report is an accompanying document for the creation of Open Music Observatory as a digital infrastructure on the World Wide Web.

The Open Music Observatory is a digital service provider for the music industry that follows the European Interoperability Framework (EIF) definition for such services with a unique governance model. The governance model and the digital service infrastructure represent a unique innovation that considers many good examples from the European Union and other industries.

An observatory has traditionally been a permanent location for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. In the past 30 years, it has also been used for long-term digital data collection programs for markets, social sciences, and humanities. Our milestone requires the start of this observatory after a lengthy and intensive planning and prototyping phase. It can be seen as a modern reimagination of the data observatory model, or the observatory 2.0. We created a new observatory model that fully aligns with the European Interoperability Framework but extends the governance of the digital services beyond public bodies, and allows the creation of a public-private partnership to manage the observatory.

We were informed and influenced by the creation of Europeana (which started out from a similar collaborative project) and their new plans to extend their digital services into the European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCCH). We aim fully interoperability with Europeana and ECCCH, but we also bring a new element into their thinking. While they are mainly aggregating the work of public sector memory institutions, we are building a governance model that allows a more successful cooperation among the private sector and the public music sector.

By the end of 2025, we aim to create an “observatory 3.0”, which already hosts many intelligent data improvement technologies and fuels innovative applications/services in line with our project’s exploitation pathways. These services are at different maturity levels, but they could not be brought to a testable MVP without building out the minimal digital infrastructure and governance model at this milestone.

References

Antal, Dániel. 2020. ‘Feasibility Study on Promoting Slovak Music in Slovakia & Abroad’. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6427514.

Antal, Dániel, Michal Grochal, and Christos Varvantakis. 2024. ‘Building a Music Data Sharing Space with Wikibase’. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8046977.

Antal, Dániel, Ádám Lázár, and Andor Kornél Barát. 2024. ‘Open Music Observatory. Progress Report’. Digital Music Observatory. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11564114.

Bianchini, Carlo, Stefano Bargioni, and Camillo Carlo Pellizzari di San Girolamo. 2021. ‘Beyond VIAF Wikidata as a Complementary Tool for Authority Control in Libraries’. Information Technology and Libraries 40 (2). https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v40i2.12959.

BVDA. 2023. ‘Data Sharing Spaces and Interoperability’. Edited by Antonio Kung (Trialog), Ray Walshe (DCU), and Rigo Wenning (ERCIM). BVDA.

Curry, Edward. 2020. ‘Dataspaces: Fundamentals, Principles, and Techniques’. In Real-Time Linked Dataspaces: Enabling Data Ecosystems for Intelligent Systems, 45–62. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29665-0_3.

D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Strong Ideas. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/.

Diefenbach, Dennis, Max de Wilde, and Samantha Alipio. 2021. ‘[Wikibase as an Infrastructure for Knowledge Graphs: the EU Knowledge Graph]{.nocase}’. In ISWC 2021, 12922:631–47. Online, France: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88361-4\37.

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission), Pere Brunet, Livio De Luca, Eero Hyvönen, Adeline Joffres, Peter Plassmeyer, Martijn Pronk, Roberto Scopigno, and Gábor Sonkoly. 2022. [Report on a European collaborative cloud for cultural heritage: ex – ante impact assessment]{.nocase}. LU: Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/64014.

ESS. 2017. ‘Position Paper on Access to Privately Held Data Which Are of Public Interest’. European Statistical System. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/13019146/13346094/ESS+Position+Paper+on+Access+to+privately+held+data+final+-+Nov+2017.pdf/6ef6398f-6580-4731-86ab-9d9d015d15ae?t=1511447619000.

———. 2022. Privately Held Data Communication Toolkit. 2022nd ed. Manuals and guidelines. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EU 2019/1024 Open Data Directive. 2019. Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on Open Data and the Re-Use of Public Sector Information. Official Journal of the European Union. Vol. OJ L. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/1024/oj.

EU 2022/868 Data Governance Act. 2022. ‘[Regulation (EU) 2022/868 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on European data governance and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 (Data Governance Act) (Text with EEA relevance)]{.nocase}’. EUR-Lex. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/868/oj.

EU 2024/1689 Artificial Intelligence Act. 2024. ‘[Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act)]{.nocase}’. OJ OJ L 2024/1689 (July): 1–144. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj.

European Commission. 2017. ‘European Interoperability Framework – Implementation Strategy. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament the Council the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions’. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0134.

European Commission, and Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. 2019. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2759/346720.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, M Clarke, P Vroonhof, J Snijders, A Le Gall, B Jacquemet, et al. 2020. Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a European Music Observatory : Final Report. Publications Office. https://doi.org/doi/10.2766/9691.

Fagerving, Alicia. 2023. ‘Wikidata for Authority Control: Sharing Museum Knowledge with the World’. Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Publications 5 (1): 222–39. https://doi.org/10.5617/dhnbpub.10665.

Hudobné centrum, Reprex B.V., and Slovenská národná knižnica, and Slovenský ochranný zväz autorský. 2024. ‘Memorandum o porozumení vo vzťahu k Slovenskej súhrnnej hudobnej databáze]’.

Ministerstvo kultúry SR, and Open Music Europe. 2023. ‘Memorandum o porozumení o využití výsledkov analýz otvorených politík v kontexte slovenského kultúrneho a kreatívneho priemyslu a sektorových verejných politík v spolupráci s konzorciom pre výskum a inovácie s názvom OpenMuse. $$Memorandum of Understanding on utilizing the Open Policy Analysis results of the OpenMuse Research and Innovation Consortium in the context of Slovak cultural and creative industries and sectors’ public policies$$’. https://www.crz.gov.sk/zmluva/7645338/.

Open Music Europe. 2023. ‘[Open Music Europe (OpenMusE) – An Open, Scalable, Data-to-Policy Pipeline for European Music Ecosystems]{.nocase}’. https://doi.org/10.3030/101095295.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe, research and innovation programme, under Grant Agreement No. 101095295 (Open Music Europe (OpenMusE) – An Open, Scalable, Data-to-Policy Pipeline for European Music Ecosystems (Open Music Europe 2023)). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. ↩︎

See the references (Ministerstvo kultúry SR and Open Music Europe 2023; Hudobné centrum et al. 2024) ↩︎

See on the ECCH (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission) et al. 2022) and the European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020); on connecting the (public) European Statistical System with privately-held data: (ESS 2017, 2022); and as a general legal framework the Open Data Directive and the Data Governance Act (EU 2019/1024 Open Data Directive 2019; EU 2022/868 Data Governance Act 2022). ↩︎

You can read more in less technical language about this approach in Dataspaces: Fundamentals, Principles, and Techniques (Curry 2020), and in a more technical specification in Data Sharing Spaces And Interoperability (BVDA 2023). Reprex is an affiliated member of the Big Data Value Association (BVDA). ↩︎

The knowledge graph of the European Union: (Diefenbach, Wilde, and Alipio 2021); use for cultural authority control: (Bianchini, Bargioni, and Pellizzari di San Girolamo 2021; Fagerving 2023). Our solution: (Antal, Grochal, and Varvantakis 2024). ↩︎

Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI (European Commission and Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology 2019); Artificial Intelligence Act (EU 2024/1689 Artificial Intelligence Act 2024). We were greatly informed by Data feminism (D’Ignazio and Klein 2020) on the intersectional escalation of data biases that leads to disadvantages to women, small countries, or independent repertoires. ↩︎